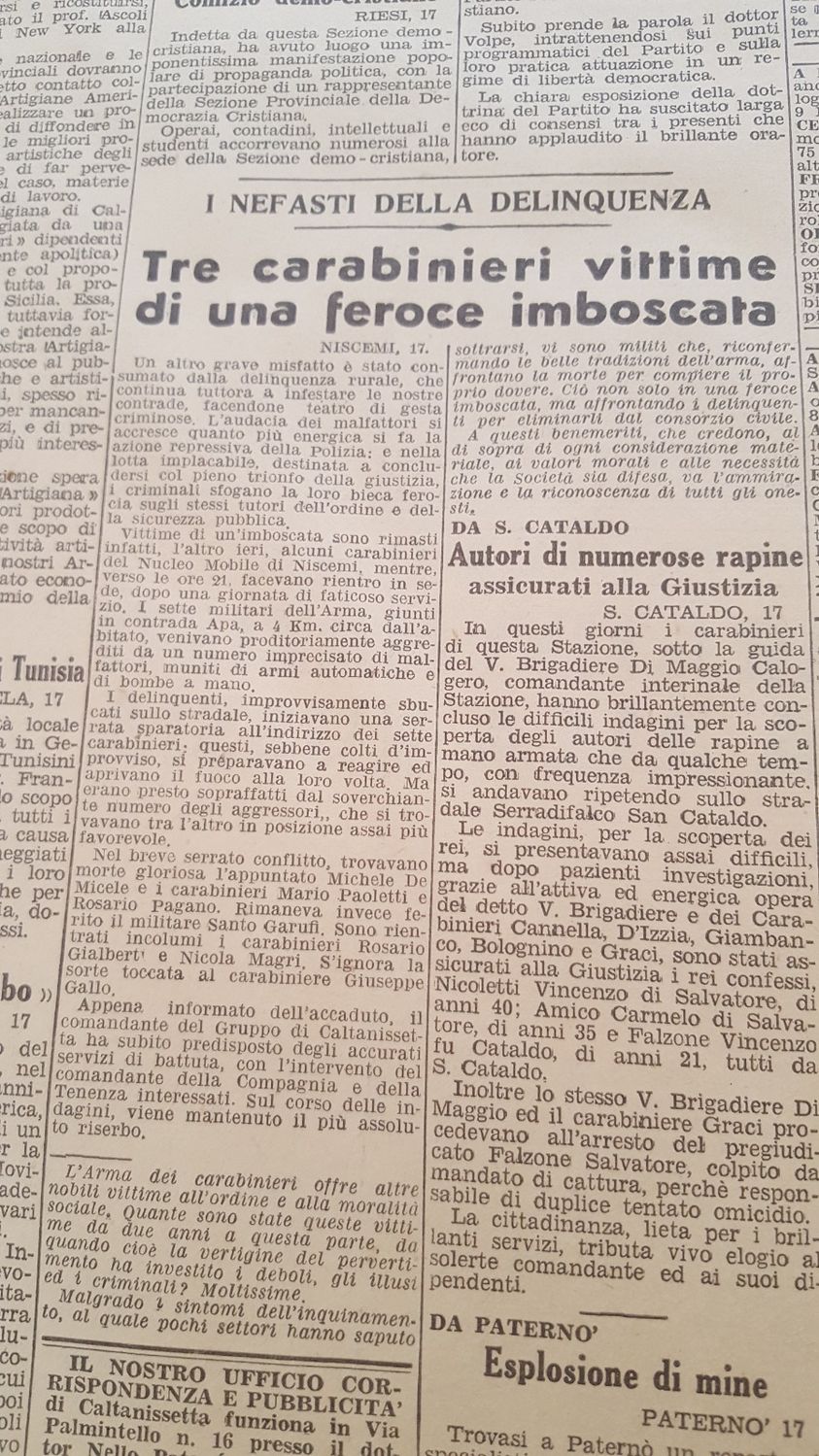

16.10.1945 Uccisi tre carabinieri in contrada Apa (Niscemi)

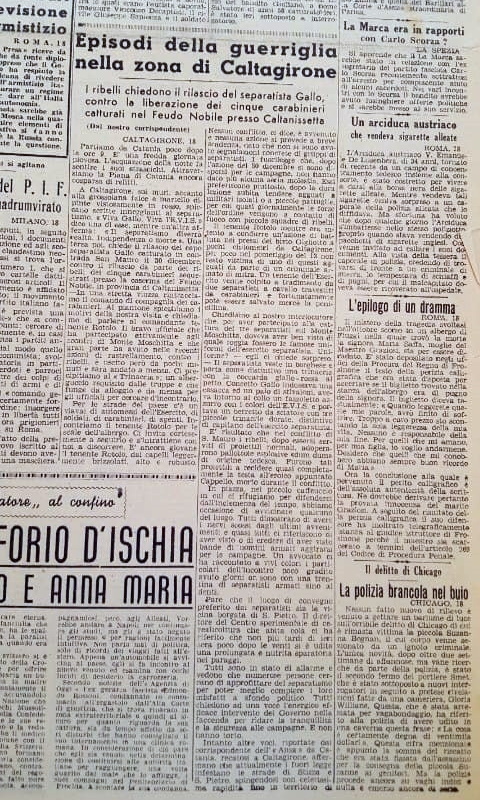

In un primo tempo la Banda dei niscemesi aveva operato nel territorio di Niscemi, razziando ciò che poteva: centinaia di persone erano state rapinate, le fattorie saccheggiate e nessuno voleva più andare ad abitare in campagna. I ricchi non uscivano più dal paese e chi si metteva in viaggio era consapevole del rischio che correva.

Farsi scortare significava solo mettere a repentaglio la vita di altre persone, soprattutto lungo la strada che conduce a Caltagirone, particolarmente battuta dai banditi.

I rastrellamenti posti in essere dai Carabinieri davano pochi frutti. Solo in un’occasione conseguirono un risultato significativo: un bandito ferito, uno catturato e un altro si costituì ai militari (il calatino Angelo Vigoroso); il tutto dopo una sparatoria nella Piana di Gela.

Verso la fine del 1945 le azioni della banda si fecero sempre più intraprendenti e costituirono un assaggio di quello che sarebbe accaduto a gennaio dell’anno dopo: la strage di Feudo Nobile.

Il 16 ottobre del 1945, una decina di banditi si appostò lungo la stradella che si diparte da quella che i Niscemesi chiamano ancora oggi “curva ri l’Apa” e conduce alla fonte che prende lo stesso nome (“bbrivatura ri l’Apa”).

Si apprenderà di seguito dalla viva voce del figlio di Canaluni che a guidare quel drappello era Giuseppe Militello (che perderà la vita in un’altra occasione sparando a un fusto di benzina nell’atto di compiere un attentato all’ingegnere Iacona).

A raccontare l’episodio vent’anni dopo sarà anche uno dei carabinieri coinvolti nell’agguato: Santo Garufi. Raggiunto anche lui alla testa da colpi di mitra, sia pure di striscio, cadde ferito e il suo corpo ricoperto da un collega morto.

I banditi si avvicinarono e il Garufi implorò loro: cosa volete più! A quel punto il Militello gridò ai suoi basta! alzando contemporaneamente la mano per stroncare ogni tentativo di aprire il fuoco.

Poi ordinò al militare di alzarsi, ma non avendo la forza qualcuno lo aiutò a farlo, sollevando il cadavere dell’ucciso che lo copriva. Un bandito gli chiese con voce perentoria: dov’è il brigadiere Montesi? Rimasero delusi nell’apprendere che non era nel gruppo.

Spiegherà Garufi che il vicebrigadiere Montesi era in forza al nucleo mobile di Niscemi ed era un vero e proprio spauracchio per i banditi. Sarà il carabiniere che per primo giungerà sul posto dove era stato fatto trovare il corpo senza vita di Canaluni.

Da questa testimonianza è facile comprendere come l’agguato mirava in realtà a far fuori il coraggioso sottufficiale. Dopo un breve conciliabolo, i banditi decisero di lasciare in vita il superstite e dopo avergli sottratto pastrano, scarpe e armi gli ordinarono di andarsene.

Con un particolare sconcertane: imposero al carabiniere ferito di togliere le scarpe ai colleghi morti. Si saprà poi che le armi sottratte (moschetti mod. 1891) furono portate a monte San Mauro e consegnate a Concetto Gallo.

Qui vennero assegnati ai Separatisti per sorteggio. Pur temendo da un momento all’altro di essere fucilato alle spalle, il carabiniere Garufi si avviò verso il paese, mentre i malviventi depredavano quel che restava dei colleghi morti.

Sebbene ferito, riuscì ad arrivare in caserma intorno alla mezzanotte e da qui fu portato in ospedale. Anche gli altri superstiti arrivarono alla spicciolata, mentre uno si portò a Caltagirone per farsi medicare in ospedale. Ne seguì un’inchiesta e grazie alle testimonianze dei superstiti si seppe che a partecipare a quell’azione di fuoco erano stati Rizzo, Buccheri, Collura, Arcerito, Romano, Bottiglieri, Lombardo, Leonardi, Interlandi e Milazzo.

Oltre ad Avila junior, il già citato Militello che fungeva da capo, un certo Buscemi, che mai venne esattamente identificato e forse qualcun altro. Pare pure che fra i banditi ci fosse l’Avila padre, ma di ciò – per via dell’oscurità – non si ebbe mai certezza.

Il bandito indicato col cognome Milazzo avrà un ruolo decisivo nel ritrovamento dei corpi dei carabinieri sequestrati a Feudo Nobile. In un primo momento venne indiziato come mandante di quell’eccidio il capo dell’EVIS Concetto Gallo, perché aveva teorizzato l’attacco contro i Carabinieri, in quanto rappresentavano lo “Stato Italiano”.

Addirittura nel rapporto redatto dal generale Branca e inviato al capo del governo Alcide De Gasperi si parla di Gallo come colui che aveva capeggiato “personalmente” il drappello di banditi (rapporto del 16.2.1946).

Al processo venne però prosciolto, perché riuscì a dimostrare che quel giorno si trovava al campo di Monte San Mauro. Avila Saro, figlio di Canaluni, venne arrestato sei mesi dopo e fece alcuni nomi dei complici (compreso il padre) omettendo di citare sia Rizzo che Milazzo.

Gesualdo Collura invece – arrestato anche lui – ammise la sua presenza nel gruppo, ma negò di avere partecipato alla sparatoria, dichiarando che si era allontanato per andare a prendere il cavallo di un altro bandito, il Milazzo.

Quest’ultimo alla fine confesserà le malefatte e confermerà i nomi dei complici. In un primo tempo si era anche fatto il nome di un altro bandito, tale Salvatore Di Franco, ma alla fine non fu neanche processato; venne trovato morto il 9 agosto 1945.

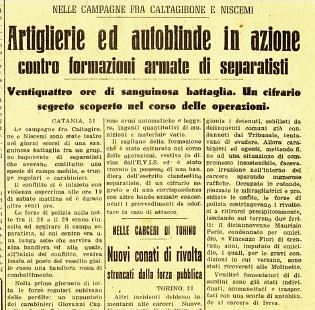

29.12.1945: La “battaglia” di Monte San Mauro

A meno di venti chilometri da Niscemi, in territorio di Caltagirone, sorge una località chiamata Monte San Mauro, ma per i Niscemesi è sempre stata “a muntagna ri san Moru”.

E’ un sito archeologico di notevole rilievo, risalente all’età del bronzo. Gli archeologi hanno ipotizzato che in passato vi fosse un’acropoli e una residenza principesca, poi riutilizzata dai Greci.

A Niscemi gli anziani raccontano una leggenda secondo la quale in quella località vi sarebbe una serie di gallerie sotterranee piene di tesori, ma chiunque vi entra e prende qualcosa di prezioso non riesce più a trovare l’uscita. Ma Monte San Mauro è noto perché fu lì che si concluse l’epopea militare dell’EVIS, con la cattura del capo Concetto Gallo.

Ma perché proprio a Caltagirone? Anche qui vi è una storia “ufficiale” e le versioni che si raccontano, che differiscono dalla narrazione canonica. Per comprendere cosa accadde e perché accadde proprio in quel luogo bisogna fare un passo indietro e tornare al momento dell’uccisione del capo militare Antonio Canepa (17 giugno 1945).

I vertici militari temettero una reazione da parte degli Indipendentisti e non solo rinforzarono le guarnigioni che davano la caccia ai Separatisti, ma misero su una rete di collaborazionisti nel tentativo di stanarli.

Ma anche il fronte opposto aveva i suoi 007, per cui vennero avvisati che il campo di Cesarò, che era la base dell’EVIS, era stato scoperto e furono costretti a migrare in fretta e furia in altro posto. Questo venne individuato proprio a San Mauro, dove la moglie di Concetto Gallo (Gueli Adriana) possedeva dei terreni.

Comunque sia, il 27 dicembre del 1945 alcuni informatori riferirono che il campo-base si trovava proprio in quella località del Calatino e una superficiale ricognizione in incognito confermò la veridicità della notizia: per l’esattezza Monte Moschitta, sud-ovest di Caltagirone, quota 530 metri (così si legge nelle carte dei militari).

Il numero dei separatisti si aggirava sulla sessantina (ma questo si verrà a sapere dopo) tuttavia il ”boccone” era prelibato perché c’era pure quel Concetto Gallo che aveva preso il posto di Antonio Canepa, il mitico Mario Turri; ed era tanta la devozione verso il defunto comandante che Gallo volle prendere il nome di battaglia di Secondo Turri. La nomina di Gallo fu fatta per acclamazione il 1 luglio del 1945: aveva appena 32 anni. E così il 29 dicembre di quell’anno iniziarono le operazioni militari con la creazione di due colonne: una (formata da 100 fanti, 200 carabinieri e due carri armati) che partendo da Catania avrebbe tentato direttamente l’assalto e l’altra formata da 200 carabinieri, proveniente da Siracusa, col compito di sbarrare l’eventuale fuga.

Concetto Gallo, come un vero capo militare, arringava spesso i suoi uomini; in un’occasione ebbe a rassicurarli dicendo loro che nel caso di cattura da parte del “nemico” i combattenti sarebbero stati trattati secondo le convenzioni internazionali in quanto i guerriglieri del GRIS erano accreditati come belligeranti.

IL GRIS (Gioventù rivoluzionaria per l’Indipendenza della Sicilia) non era altro che il nome dato all’esercito indipendentista (EVIS) dopo la morte di Canepa. Sostanzialmente ne era la prosecuzione, per cui i due termini sono da ritenersi indicanti lo stesso organismo.

Secondo quello che scrisse l’Unità alla vigilia del processo a Concetto Gallo (11 luglio 1950) fu proprio Salvatore Giuliano che qualche ora dopo l’assalto alla caserma di Bellolampo (26.12.1945) inviò un corriere a cavallo con una missiva da consegnare al Gallo, con la quale lo stesso veniva avvertito che da lì a qualche giorno l’esercito italiano sarebbe intervenuto in massa a Monte San Mauro. La missiva sarebbe stata sequestrata al capo dell’EVIS. Anni dopo il niscemese Giacomo Balistreri rievocherà quei tempi in una interventista alla Rai (al minuto7

La battaglia fu molto cruenta e furono tanti i colpi sparati che si esaurirono le munizioni, per cui il conflitto riprese l’indomani, dopo l’arrivo dei rifornimenti (che prudentemente erano stati stipati in un presidio a Caltagirone).

L’azione bellica ebbe fine intorno a mezzogiorno del giorno dopo. Al termine gli Indipendentisti catturati furono appena quattro (compreso il capo), vennero sequestrati sei mitragliatrici, 3000 cartucce, alcuni fucili e moschetti, una Fiat 1100 e alcuni capi di bestiami ritenuti oggetto di furto.

Sul campo rimase ucciso un appuntato dei carabinieri (Giovanni Cappello di Santa Croce Camerina) e quattro militari vennero feriti: il sottotenente di fanteria Giovanni Corcione, il vicebrigadiere dei carabinieri Maugeri e i fanti Giuseppe Corallo e Giuseppe Privitera. Secondo la versione dei Separatisti, ad uccidere il milite fu un proiettile sparato dagli stessi carabinieri.

Tra gli evisti perse la vita tale Emanuele Diliberto di Palermo e cinque rimasero feriti. Tra essi due banditi niscemesi. Perì anche un contadino (tale Cataudella) che cavalcava una giumenta bianca, forse scambiato per Gallo, che aveva un animale simile. Il bilancio finale si presentava tuttavia molto magro per lo Stato.

Vero è che il capo militare era stato catturato, ma era pur vero che il grosso degli evisti (e dei banditi) era riuscito a fuggire. E fra questi – si legge nel rapporto – tutti gli appartenenti alla banda dei niscemesi!

Anche le cifre appaiono impietose: da un lato 500 militari “professionisti” comandati da ben tre generali (Concetto Gallo scriverà nelle sue memorie che i generali erano cinque) contro meno di sessanta “irregolari”! Al momento dell’interrogatorio Gallo fece delle parziali ammissioni, ma si rifiutò di rivelare particolari compromettenti.

Ammise di essere il capo e che obbediva a un comando supremo, senza aggiungere alcun dettaglio, escludendo sdegnosamente che gli assalti alle caserme del Palermitano fossero riferibili ai separatisti e che la presenza dei briganti nel campo era solo occasionale e fortuita.

Quanto al finanziamento delle “truppe”, rispose che i proventi derivavano da donazioni spontanee e da “requisizioni” che egli stesso ordinava.

L’organizzazione della vita all’interno del campo è stata descritta da diversi partecipanti: il capo era Gallo, che si faceva chiamare comandante e il suo vice – che aveva il grado di tenente – era quel Nino Velis che poi prenderà il suo posto.

Tutto il campo era attorniato da posti di controllo armati di mitragliatrici e 24 ore su 24 vi era una pattuglia di ispezione.

Alle dirette dipendenze di Gallo e Velis vi erano dei “sergenti” e sotto ancora dei “caporali”. Quando venne interrogato il Gallo – probabilmente per darsi più importanza – affermò che il suo “esercito” era composto da varie brigate di cento uomini ciascuna e che ogni brigata comprendeva dieci squadre.

Nonostante le precauzioni prese, qualche estraneo sconfinava nel campo. In questo caso era stato predisposto un protocollo alquanto singolare: temendo che potesse trattarsi di infiltrati o carabinieri in incognito, chi veniva colto nei paraggi doveva essere catturato, bendato e condotto al cospetto del comandante.

Durante il percorso – e qui sta la singolarità – gli evisti dovevano confabulare fra loro, ma facendosi sentire dai catturati, evocando carri armati, pezzi di artiglieria e altri particolari non veritieri, al fine di portare all’esterno un’immagine molto più potente di quell’”esercito”.

Si apprese pure che qualcuno in piena notte “disertò” e per questo fu inseguito, temendo una delazione. Si seppero anche i nomi: Umberto Camuri, Francesco Paolo Ghersi e Umberto Siracusano.

Altro stratagemma da usare in caso di battaglia (cosa che poi avvenne) era quello di spostare in continuazione le armi a ripetizione, al fine di dare la sensazione che esse fossero di gran lunga superiori a quelle effettive. Questa tattica in effetti ebbe qualche risultato: gli “Italiani” si convinsero che il primo scontro era avvenuto solo con un avamposto e non con l’intero “esercito”.

Il racconto di Concetto Gallo

Quando Concetto Gallo, il capo militare dell’EVIS catturato a Monte San Mauro, anni dopo si decise a parlare, riferì che quando si trasferì a Caltagirone trovò la zona “infestata”, soprattutto dalla banda dei Niscemesi, sebbene qualche altro fuorilegge locale ci bazzicasse pure.

Allora cominciò a prendere contatto con le varie compagini criminose, siglando dei patti di non belligeranza ai quali molti aderirono.

Raccontò anche di un caso di conflitto a fuoco tra Separatisti e banditi e qualcuno di questi ci lasciò le penne. In effetti il 22 giugno del 1945 sul monte Soro, la cima più alta dei Nebrodi, l’evista Francesco Ilardi con altri commilitoni ebbe uno scontro a fuoco con la banda di Giovanni Consoli che, abusando del nome dell’EVIS, compiva estorsioni. “E le forze dell’ordine si fecero belle…” concluse ironicamente.

Qualche malvivente addirittura si presentò come volontario nel campo e a quel punto Gallo doveva scegliere, non potendo lottare tra due fronti: banditi e carabinieri.

Parlando poi della banda Canaluni disse che una volta fece legare nudo a un albero proprio Rosario Avila perché si era comportato male.

Ovviamente non sappiamo quanto di vero ci sia nelle sue parole. Così come non possiamo essere certi che affermi il vero quando dichiara che “il bandito Rizzo, dipinto come un uomo feroce, era in effetti servizievole e devotissimo”.

In un’intervista concessa dopo tantissimi anni parlerà anche degli introiti derivanti dalla vendita del suo olio, aggiungendo che dopo la battaglia ne scomparvero ben 25 quintali. A chi poi donava generi di prima necessità veniva rilasciata una ricevuta con il timbro dell’Evis e la firma del Gallo con lo pseudonimo “M.Turri”.

Le ricevute erano numerate e datate e in ognuna veniva specificato se le donazioni erano “volontarie” oppure “forzate”. Ovviamente furono incalzanti le domande sulla commistione separatisti-banditi.

La risposta del Gallo fu molto evasiva: parlò di sei “malfattori” che erano stati accolti nel campo, ma che al momento della battaglia la metà era andata via, mentre chi rimase prese attivamente parte al conflitto. Ammise che durante la notte i banditi uscivano dal campo per commettere reati, ma per quanto a sua conoscenza non si accompagnavano agli evisti nelle scorrerie.

Quanto ai momenti del suo arresto, ricorda di essere stato stordito da una bomba e di essersi ritrovato bloccato da alcuni carabinieri. Infine conferma il numero esatto dei suoi “soldati”: 53 più 3 banditi.

Addosso a Gallo fu rinvenuto un cifrario, diverse lettere a firma “Vento”, una tessera falsa intestata a certo Franco Buscemi e una patente falsa.

In una di queste lettere, datata 2 dicembre 1945, uno sconosciuto, del quale Gallo si rifiuterà di fare il nome, lo avvertiva che cinquecento uomini erano stati inviati contro di lui (a dimostrazione che l’Evis aveva un servizio di intelligence). A conferma che il Gallo dipendeva da un “comando supremo” la lettera così concludeva: in caso di successo prima di proseguire avverti e attendi ordini.

Ci sono voluti quasi trent’anni perché Gallo rivelasse l’autore di quella missiva: in un’intervista rilasciata nel 1974 dirà che il capo del comando militare da cui dipendeva e perciò l’autore di quella missiva che gli preannunciava l’attacco e che si fermava “Vento” era Guglielmo Carcaci, separatista e nobile, appartenente a quell’ala politica che per convenzione viene chiamata “di destra”.

In parallelo erano in corso trattative tra il MIS e il governo italiano: a Roma col ministro Romita e a Palermo col generale Berardi, comandante militale dell’Isola.

https://www.facebook.com/100000409642786/videos/1174175145939462/

I Separatisti erano consapevoli che la situazione poteva precipitare in un bagno di sangue e così prospettarono all’alto ufficiale l’idea di mettere sul piatto dell’accordo una vasta amnistia, specie in favore dei giovani che avevano aderito all’EVIS (o GRIS che dir si voglia), lasciando fuori dal provvedimento di clemenza i banditi e lasciando soprattutto le forze di repressione libere di agire verso costoro.

Queste trattative semiclandestine diedero l’impressione che il generale fosse persona debole, al punto da ritenere che lo scontro di monte San Mauro non avrebbe ottenuto l’esito sperato perché gli ordini impartiti sarebbero stati quelli di tenere un comportamento blando, senza forzare la mano.

Il Carcaci peraltro aveva raggiunto con quest’ultimo un accordo: non ci sarebbe stato alcun intervento militare nel campo di San Mauro sino a quando erano in corso le trattative. Ma così non fu.

E quando l’assalto avvenne, Carcaci si precipitò a muso duro dal generale, il quale si scusò dicendo che l’ordine era stato dato da Aldisio, approfittando della sua assenza dall’Isola.

Questo è quel che racconta in un’intervista, nella quale ripercorre quel che accadde quel giorno e il racconto appare intriso di autoreferenzialità per la narrazione di momenti eroici probabilmente mai avvenuti.

Gallo parla di un proiettile che lo colpì al petto, ma venne deviato da una medaglietta, di un colpo di mitra che si limitò a sbucare il giaccone e di un colpo di fucile che gli fece volare il berretto, lasciandolo indenne.

A questo punto, vista la fine imminente, decise di suicidarsi, estraendo dalla tasca una bomba a mano e lanciandosela ai piedi.

Ma la bomba non esplose. Continua il suo racconto romanzato: svenni e un militare era sul punto di spararmi una raffica di mitra, quando intervenne il maresciallo Manzella, che rivolto al milite disse “se tiri contro quell’uomo ti ammazzo”.

Fu quindi ammanettato e condotto in cella, dove rimase da solo per due giorni, senza cibo né acqua. Assieme a lui vennero catturati due indipendentisti: Amedeo Boni e Giuseppe La Mela.

Raccontò anche un episodio inedito: uno dei generali che comandavano le truppe si complimentò con suo padre (anch’egli separatista ed eletto sindaco di Catania negli anni Cinquanta) dicendogli ho avuto l’onore di stringere la mano a suo figlio.

Si tratta di verità o di invenzione messa in giro per creare un mito? Non si saprà mai: di certo i suoi lo veneravano, al punto di soprannominarlo u liuni di santu Mauru.

Tra i protagonisti della battaglia il niscemese Totò Salerno.

Nell’intervista rilasciata da Gallo viene ricostruito come, quando e perché avviene l’incontro con i “banditi” e con Giuliano in particolare. Per come anticipato, tutto accade dopo la morte del primo capo dell’Evis, Antonio Canepa.

Questo il racconto di Gallo, che parla in prima persona: Il 17 giugno, mentre sto per lasciare Catania, ricevo una telefonata da Guglielmo duca di Carcaci, comandante della Lega giovanile e comandante generale dell’EVIS.

Mi dice: « Hanno ammazzato Canepa. Non ti muovere. Ti verrò a prendere io ». Partimmo insieme verso Cesarò e ci rifugiammo nella ducea di Wilson, presso Bronte. Trascorsi alcuni giorni, arriva un’automobile. Alla guida c’è un ammiraglio della marina degli Stati Uniti.

Accanto una bella signora. Dietro, Guglielmo di Carcaci con in testa un cappello da commodoro (una sorta di ammiraglio -n.d.a.). Entro in fretta e furia nell’automobile, m’infilo una giacca da ammiraglio degli Stati Uniti, metto in testa il berretto da commodoro e l’automobile s’avvia.

La città è circondata da polizia e carabinieri. Un vero presidio con posti di blocco ovunque. Ovunque uomini e barriere che si alzano solo dopo che la polizia ha controllato i documenti di chi vuole lasciare la città. Noi arriviamo al posto di blocco di Ognina. L’ammiraglio si fa riconoscere e la pattuglia dei carabinieri ci fa un perfetto saluto aprendo la barriera.

Qui Gallo e gli altri vengono ospitati dal comando militare degli USA e qui parla con uomini dei Servizi Segreti a stelle e strisce. Ne nasce una riflessione ad alta voce: gli Americani vedono di buon occhio il movimento separatista! Il racconto continua poi con l’incontro tra lo stesso Gallo e il capo della banda, il “mitico” Salvatore Giuliano.

Tutto nasce da una riunione a Palermo, nel corso della quale gli indipendentisti si dividono in due fazioni: chi intende rinunciare alla lotta armata e chi invece vuole mantenerla sino ad ottenere l’indipendenza.

Alla fine non viene presa alcuna decisione. A quel punto il Gallo chiede ad un altro esponente di rilievo del Movimento, il conte Tasca, di incontrare Giuliano al fine di trovare una sistemazione dei giovani dell’EVIS nella sua zona, nel caso di necessità.

La risposta è ironica: sì, ora fai il numero di telefono e ti risponde Giuliano. Il giorno dopo Gallo – assieme ad altre tre persone – si mette a girare alla ricerca del bandito imprendibile.

Ci riesce: incontra Giuliano e si meraviglia di vederlo solo, visto che i giornali lo descrivono come accompagnato sempre da guardie del corpo. I due si conoscevano reciprocamente solo di fama: si salutano e ben presto nasce un rapporto di rispetto, che diventa subito simpatia.

Ma i due hanno un passato e anche un presente diversi e questa differenza la si coglie anche nel linguaggio relazionale: Gallo dà del tu a Giuliano e questi contraccambia col classico Vossia. Ora io dormo un’ora e vossia fa la guardia. Poi, quando io mi sveglio, si appisola vossia. E gli consegna il mitra. Ha così inizio il matrimonio tra la banda e l’Evis.

I due stanno assieme due giorni e si lasciano con queste parole pronunciate da Concetto Gallo: Io ti prometto che se tu in questa lotta ti comporterai bene, dimenticando tutto il resto e guardando all’ideale dell’indipendenza, soltanto a quello, ti prometto che se vinceremo noi avremo una giusta considerazione per te e tu sarai giudicato per quelle che sono le tue vere colpe.

Gallo – a distanza di quasi trent’anni – vuole marcare ancora le distanze. Si dilunga molto su questo punto.

E racconta di avere voluto tenere ben distinti gli scopi delle due compagini: vedi, tu sei qua sopra le montagne per i tuoi motivi; noi siamo sulle montagne per altri motivi.

Noi potevamo stare benissimo nelle nostre case. Invece abbiamo deciso di batterci per un ideale di libertà e di indipendenza. Libertà e indipendenza che se la Sicilia avesse avuto prima, avrebbero inciso sul suo sviluppo economico e, certamente, tu, oggi, non saresti qui, in questa situazione.

L’arrivederci del Gallo sarà in realtà un addio e dopo un abbraccio Turiddu lo rassicura. A modo suo: Cu tocca a vossia mori.

I dubbi sul racconto di Gallo

Quanto ci sia di vero nel racconto dell’ex capo militare non è dato sapere; certamente dice il vero quando afferma che l’Evis aveva bisogno di tranquillità per operare come esercito clandestino e non poteva certo farsi schiacciare dai rastrellamenti dei carabinieri da una parte e dalle scorrerie dei banditi dall’altra.

Fu dunque una scelta tattica più che strategica o organica, che dir si voglia. Di certo poi fantasioso fu il numero dei militari italiani che dovette affrontare a San Mauro: parla di cinquemila uomini (in realtà la cifra va ridotta del 90 %), di cinque generali (in realtà furono tre), di aerei di ricognizione e di tanto altro.

L’intervista si fa “bollente” quando viene toccato il tema della mafia. Non nega Gallo che anche don Calo’ Vizzini aderì al MIS, anzi pare andasse in giro con lo stemma della Trinacria. Ma tale adesione strumentale durò molto poco: ben presto la Mafia – sono parole di Gallo – traghetterà in un ben preciso partito politico. E poi non aveva alcun senso militare in un gruppo che non aveva potere…

E i giudizi verso la Mafia non sono per niente entusiastici, arrivando a narrare di una larvata minaccia proferita nei suoi confronti dal mafioso di Villalba: Stai attento perché uno di questi giorni ci potrai lasciare la pelle. Stai attento.

In effetti in un rapporto della polizia di Palermo si legge testualmente: la Mafia ha abbandonato il MIS. Infine smentì ogni contatto con la Casa Savoia, qualche volta adombrato dagli storici. Sul luogo dello scontro Concetto Gallo fece erigere un monumento per ricordare la battaglia e i caduti per la “causa siciliana”.

Tra i sopravvissuti di monte San Mauro, da annoverare fra gli idealisti puri dell’Indipendentismo, anche un (allora) giovane di Niscemi, morto nel 1994: Totò Salerno.

Con Giacomo Balistreri e Santo Benintende risultano essere i Niscemesi più noti che aderirono al Separatismo, senza avere nulla a che fare con i banditi.

Salvatore Salerno faceva il campiere per conto di una famiglia di possidenti di Niscemi e mentre girava per le campagne in una masseria incontrò Concetto Gallo: da quell’incontro rimase stregato dalla fede separatista.

Agendo con discrezione, faceva continui viaggi da Niscemi a San Mauro per rifornire di merci (soprattutto generi alimentari) che gli venivano consegnate da un possidente di Niscemi. Quando il 29 dicembre del 1945 avvenne lo scontro con i militari “italiani”, riuscì a scappare, favorito anche dalla folta nebbia, portando con sé un cimelio di notevole interesse storico, ancora conservato dagli eredi: la bandiera dell’EVIS con lo stemma della trinacria e nove strisce, di cui cinque gialle e quattro rosse.

La bandiera era stata consegnata a Concetto Gallo da Lucio Tasca e dal duca di Carcaci in occasione di un incontro a Palermo. Racconta Orazio Barrese nel libro “La guerra dei sette anni”: nel severo salone di una vecchia casa palermitana, dalle mani di quelle donne gentili, la bandiera passò in quelle di Guglielmo, che solennemente la consegnò a Concetto.

Questi, commosso, col ginocchio a terra, la baciò pronunziando le parole del giuramento mentre gli astanti sommessamente cantavano la nostalgica preghiera “Oh Diu, ascuta la priera di la genti siciliana, binirici la bannera di la nostra libbirtà”.

Secondo quel che raccontano Paolo Sidoni e Paolo Zanetov (Cuori rossi, cuori neri) al momento della battaglia di monte San Mauro Concetto Gallo portava quella bandiera attorno al collo.

Con una particolarità che al valore storico unisce un valore affettivo: la presenza di piccole macchie di sangue di qualcuno rimasto ferito durante lo scontro (forse dello stesso Gallo).

Nonostante l’attività semiclandestina del Salerno, egli era stato ben individuato dai Carabinieri; tuttavia nei confronti dello stesso non venne applicata alcuna misura.

Fu invece fermato – e poi rilasciato in quanto del tutto estraneo – subito dopo il rapimento dei Carabinieri e l’attacco alla caserma di Feudo Nobile, che fu opera esclusiva della banda Avila-Rizzo.

Nel corso della sua permanenza a Monte San Mauro ricevette delle confidenze secondo le quali la banda Canaluni si accingeva a sequestrare uno dei più ricchi possidenti di Niscemi, ma poi tutto fallì, probabilmente perché l’obiettivo dei banditi si era spostato verso i carabinieri di Feudo Nobile.

Nella foto la bandiera originale con le macchie di sangue in possesso di un niscemese –

Concetto Gallo e i banditi niscemesi

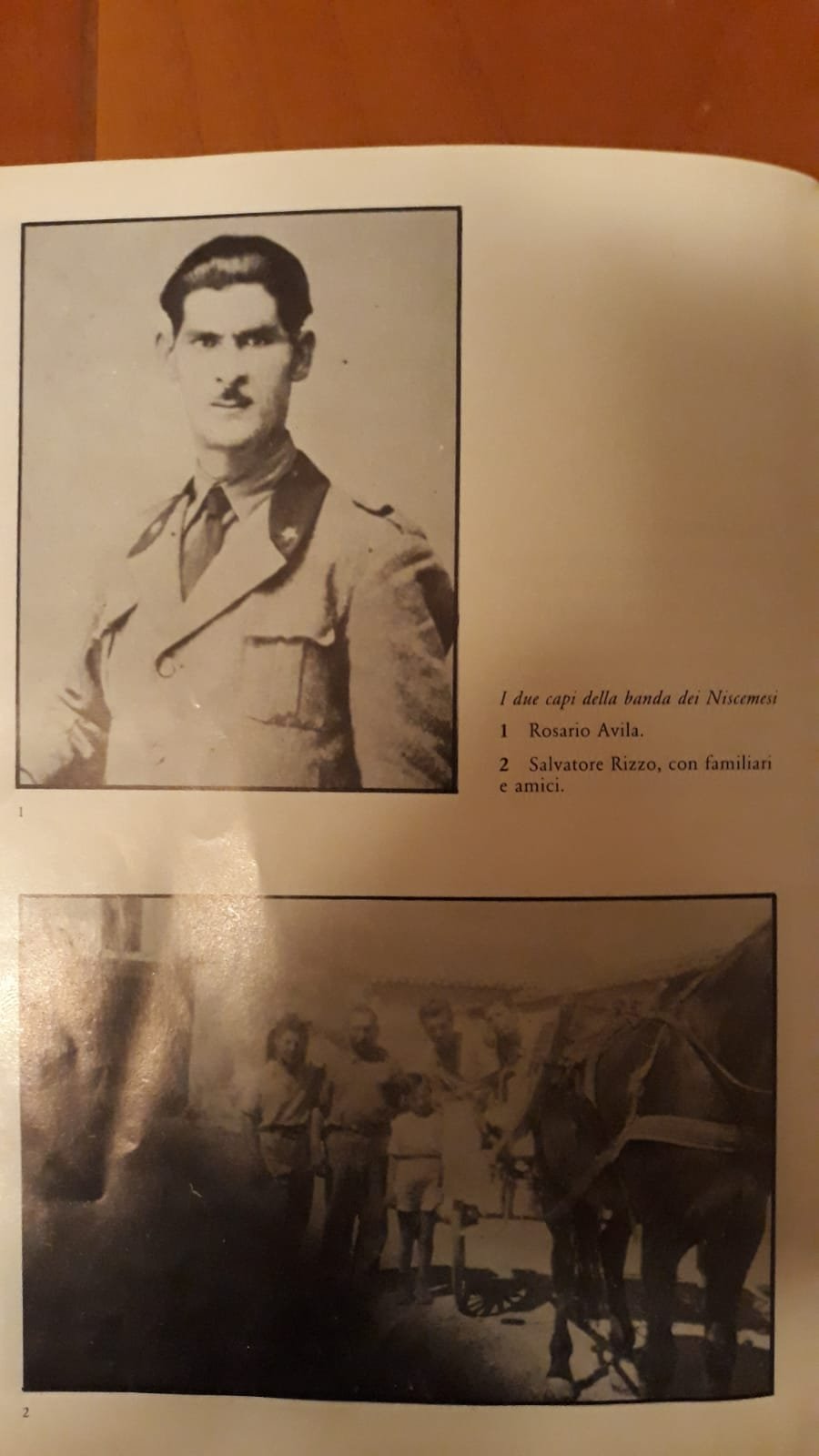

Accanto ai Separatisti a san Mauro c’erano anche i fuorilegge niscemesi, quelli della banda Avila-Rizzo. Anzi, secondo il racconto di molti, erano proprio quelli che attorniavano di più Concetto Gallo, quasi venerandolo.

Si calcola che vi stazionassero da dodici a venti banditi, compreso l’ergastolano Saporito e alloggiavano in posti separati rispetto a chi aveva abbracciato la fede indipendentista. Da costoro venivano considerati come dei contadini sfortunati, ingiustamente perseguitati dallo Stato italiano.

Secondo l’accusa (sentenza della sezione istruttoria della corte di appello di Palermo del 23.12.1947) al momento dello scontro erano presenti i seguenti banditi: Avila padre e figlio, Arcerito Vincenzo, Rizzo Salvatore, Collura Gesualdo, Buccheri Vincenzo (tutti di Niscemi), Romano Giacomo, Bottiglieri Angelo, Interlandi Ignazio, Lombardo Giuseppe (tutti di Caltagirone) e Leonardi Luigi (non meglio identificato)

Al primo interrogatorio Gallo ammise di averli ospitati “per necessità di vita”, indicando in sedici il loro numero e specificando che solo in tre presero parte attiva al conflitto a fuoco del 29 dicembre.

Addirittura in un primo momento non si conobbero le esatte generalità dei Niscemesi, ma solo il nomignolo: Totò detto l’elefante, per la sua andatura dondolante, descritto nei verbali come un uomo di circa 35 anni con baffetti e pizzo, Ziu Nzulu, di bassa statura con baffi castani, Ziu Luigi, dalle basette folte e la barba rossiccia, Rafanazza, un tipo basso, nero in viso e sempre sospettoso.

E c’era pure l’adranita “Lavanna ri pudditru”, al secolo Giuseppe Milazzo, un uomo alto, sdentato e calvo, che avrà un ruolo decisivo nella individuazione dei cadaveri degli otto carabinieri di Feudo Nobile.

In realtà oltre ai Niscemesi “idealisti” (che cioè avevano aderito all’EVIS solo per pura ideologia) vi partecipò un piccolo gruppo di banditi, che riuscì a scappare rifugiandosi nel bosco di Santo Pietro, dove vi era un covo della banda.

Alcune fonti riportano che Avila padre e figlio risultavano iscritti nella sezione di Niscemi dell’EVIS, ma si tratta di un’affermazione mai provata. Anzi appare poco credibile, visto che la quasi totalità dei Niscemesi vedeva la banda come fumo negli occhi per via della ferocia e della tracotanza; il che avrebbe allontanato le simpatie dei tanti aderenti al movimento separatista.

Da fonti del ministero dell’interno si disse pure che erano state trovate le tessere di adesione di padre e figlio: la prima datata 8.3.1944 e la seconda datata 28.4.1945.

Nessuno invece ha mai parlato dell’altro capo – Rizzo – come iscritto al MIS.

La presenza dei banditi nel campo suscitò malumori fra i giovani del GRIS, non comprendendo bene a che titolo fossero là e soprattutto cosa c’entrassero con gli ideali per cui costoro combattevano.

Allora venne messa in giro la voce che il comandante Gallo aveva stipulato con loro un accordo, in base al quale essi avrebbero cessato ogni attività criminale privata e si sarebbero messi al servizio dell’Indipendentismo.

Se quest’ultimo avesse trionfato, sarebbe stata promulgata un’amnistia per quanti sino ad allora si erano macchiati di gravi reati. Inoltre la presenza veniva giustificata con la conoscenza approfondita dei luoghi che i fuorilegge avevano: circostanza che poteva tornare molto utile nel caso (quasi certo) di uno scontro con le forze “italiane”.

E poi c’era da considerare che contro quegli uomini vi erano solo delle accuse non suffragate da alcuna sentenza e non era quello il luogo o il tempo per sostituirsi ai tribunali…Queste spiegazioni rabbonirono un po’ gli animi, pur permanendo qualche diffidenza tra Separatisti e Banditi: i primi consideravano i secondi come manovalanza e come tale li trattavano.

A distanza di tanti anni esiste ancora un Movimento indipendentista, sebbene con pochissimi proseliti e quel che più contestano a Gallo è proprio l’avere accolto indiscriminatamente nell’Evis dei banditi. E tra i più efferati quelli della cosiddetta Banda dei Niscemesi.

10 gennaio 1946 i banditi assaltano la caserma di Feudo Nobile

Feudo Nobile è una località situata in territorio di Gela, ma la maggior parte dei terreni – all’epoca dei fatti – erano coltivati da Niscemesi e Vittoriesi.

Distese di viti da cui si ricavava (e si ricava)un ottimo vino (ancora oggi utilizzato per produrre il Cerasuolo) con tante case sparse, al punto che sino agli anni Settanta del secolo scorso vi insisteva la “scuola rurale”: ogni giorno i bambini venivano condotti in una cascina e lì un insegnante impartiva le lezioni.

Approssimativamente è equidistante da Gela, Niscemi e Vittoria e perciò punto strategico dove posizionare una delle tante caserme dell’Arma. Aveva un contingente di nove uomini; a comandarla il brigadiere Vincenzo Amenduni, allora trentanovenne, originario della Puglia.

Tutti erano consapevoli che si trattava di un presidio esposto alle rappresaglie dei banditi che infestavano la zona e in particolare quelli legati a Canaluni.

Per le bande la parola d’ordine era “assaltare le caserme”; a correre maggiori rischi erano ovviamente quelle piccole, specie se collocate in posti isolati: proprio come quella di Feudo Nobile.

L’allarme è alto, ma non si possono abbandonare i presidi, proprio in un momento così critico. Il 29 dicembre 1945 c’era stata la battaglia di Monte San Mauro e tre giorni prima una cinquantina di uomini del bandito Giuliano aveva sferrato un attacco in grande stile alla caserma di Bellolampo, una frazione di Palermo.

Il 9 gennaio 1946 dei contadini bussarono alla caserma di Feudo Nobile per denunciare un furto di bestiame in una località chiamata “casa Bonvissuto”.

L’indomani quattro militari e il comandante uscirono per un sopralluogo e una ricognizione. Si accingevano a ritornare in caserma, quando videro dei contadini fuggire al grido “i banditi, i banditi”. All’orizzonte apparve un gruppo di fuorilegge a cavallo armati di tutto punto.

Probabilmente alla testa della squadriglia c’era il famigerato Salvatore Rizzo. I cinque militari si rifugiarono in un casolare e si prepararono a resistere all’assalto dei malviventi.

Ne nacque un lungo e aspro conflitto a fuoco, ma le due fazioni, quanto ad armi, si rivelarono sbilanciate. I banditi ne avevano in abbondanza e possedevano anche delle granate: apparve subito chiaro quale poteva essere l’esito di quella piccola battaglia! Ma le cose andarono veramente così?

Fine della storia

Finiva così la storia del brigadiere Vincenzo Amenduni e dei carabinieri Fiorentino Bonfiglio (28 anni), Mario Boscone (22 anni) , Emanuele Greco (25 anni), Giovanni La Brocca (20 anni), Vittorio Levico (29 anni), Pietro Loria (22 anni) e Mario Spampinato (31 anni).

Al brigadiere Amenduni verrà concessa postuma la medaglia d’oro con decreto presidenziale n. 98 datato 5 aprile 2016, con la seguente motivazione: <Con ferma determinazione, esemplare iniziativa ed eccezionale coraggio, nel corso di un servizio perlustrativo, unitamente ad altri militari, non esitava ad affrontare un soverchiante numero di fuorilegge, appartenenti a pericolosa banda armata>.

Fatto segno a proditoria azione di fuoco, replicava con l’arma in dotazione, dopo aver trovato rifugio all’interno di un fienile, resistendo strenuamente sino al termine delle munizioni, allorché’ veniva catturato. Costretto a marcia forzata nell’agro Nisseno per 18 giorni, sottoposto ad atroci sofferenze fisiche, ininterrotto digiuno e vessazioni, veniva, infine, barbaramente trucidato.

Chiaro esempio di elette virtù militari e altissimo senso del dovere». Ex feudo Nobile, agro di Gela (Caltanissetta) – Ex feudo Rigiulfo, agro di Mazzarino (Caltanissetta), 10 – 28 gennaio 1946.

Con identica motivazione vennero concesse medaglie d’oro alle altre vittime di questa barbarie.

In un primo momento tutte le indagini afferenti la banda dei niscemesi vennero concentrate presso la procura di Palermo, ritenendo che gli ordini fossero venuti proprio dal Capoluogo; successivamente la maxi-inchiesta venne smembrata e gli atti inviati per competenza alle varie procure dell’Isola, secondo il luogo dove i delitti erano stati commessi: si perse così la visione globale degli accadimenti.

Molti dei banditi verranno processati nel dicembre del 1948 davanti la corte di assise di Caltanissetta per i fatti di Feudo Nobile e saranno condannati all’ergastolo: saranno solo i banditi a pagare, essendo escluse altre responsabilità.

Anzi fu espressamente sancito che l’ideale indipendentista per i banditi era solo di facciata. Così letteralmente scrive la Corte: la predetta banda (composta tutta da avanzi di galera, di evasi e di pregiudicati) successivamente si aggregava al GRIS al solo intimo proposito di mascherare e rafforzare il raggiungimento delle proprie finalità, rivolte unicamente alla consumazione dei più gravi delitti.

Dunque nessuna patente di “idealisti” per i feroci fuorilegge di Niscemi. Probabilmente più che le sentenze ad essere carenti furono le indagini: non si sa se consapevolmente. Si ebbe (e si ha tuttora) la sensazione di avere voluto chiudere frettolosamente quel periodo, senza tanti approfondimenti.

In occasione della decisione emessa contro Concetto Gallo il 28.10.1950, la Corte evidenziò in un inciso, tanto sintetico quanto efficace, tutte le sue perplessità, mettendo in rilievo la non lodevole superficialità degli accertamenti.

Per il resto ratificò il carattere politico di tutte le azione di Concetto Gallo e in special modo i fatti di monte San Mauro: l’ambiente è quello della battaglia che vede contrapposti due piccoli eserciti, il regolare comandato da tre generali e quello dei ribelli contro l’ordine costituito comandato da Concetto Gallo, che agiva per un ideale, sia pure condannevole, per il sovvertimento che si proponeva, ma pur sempre un ideale.

Tutti i reati erano pertanto da ritenersi inclusi nel decreto di amnistia, compreso l’omicidio dell’appuntato Cappello, derubricato da “volontario” a “preterintenzionale”. Ne conseguì la revoca dell’ordine di cattura.

Su sollecitazione dei famigliari del militare, la sentenza sul punto venne impugnata e nel processo che si svolse a Lecce – con sentenza del 18.11.1954 – rivisse l’originario capo di imputazione, sebbene vennero riconosciute molte attenuanti; alla fine Gallo fu condannato a 14 anni di reclusione, solo per questo fatto, essendo ogni altra imputazione superata dal passaggio in giudicato della sentenza di primo grado.

La pena per Gallo fu interamente condonata. Il 28 aprile del 1947 l’ispettore Ettore Messana, nel relazionare al ministero dell’Intero, scriveva con soddisfazione: sono lieto ora di potere affermare che la tenacia e lo sprezzo costante della vita di cui ha dato prova il personale dell’Ispettorato in operazioni quanto mai difficili e pericolose hanno avuto ragione della banda dei niscemesi, oramai del tutto debellata, se non si tiene conto degli ultimi due residuati -il Buccheri e il Collura – sulle cui tracce sono già i dipendenti reparti.

https://www.facebook.com/100000409642786/videos/1174833865873590/

Il 16 marzo 1946 è un sabato e la corriera partita da Catania arriva a Niscemi dopo avere fatto il giro di diversi paesetti. Deve raggiungere Licata passando da Gela.

Dopo attraversato il paese, proveniente da Caltagirone, arriva in piazza Vittorio Emanuele; qui scendono parecchie persone, altre ne salgono e fa il giro puntando verso Gela, percorrendo il breve tratto di via Umberto, via Ponte Olivo e imboccando la strada provinciale che porta al bivio che conduce alla città del Golfo.

Alla guida c’è Angelo Randazzo, dipendente della ditta di trasporti, che tante volte aveva fatto quel percorso. Sembrava un viaggio come un altro, ma ecco che dopo avere percorso circa tre chilometri arriva alle curve che immettono nel rettilineo di quella località che ancora ora viene chiamata “a valanca ro pannu” ed è costretto a fermarsi per la presenza a terra di una persona che sembra inanimata; scende dal mezzo e si accorge che in effetti si tratta di un cadavere.

Scendono increduli tutti gli altri passeggeri: un uomo robusto e possente, di sicuro molto alto giace a terra senza segni di vita. Il cadavere appare circondato da una corona di pietre, che all’altezza della testa formano una croce. Il petto si presenta sconquassato da un evidente colpo di arma da fuoco, verosimilmente sparato a distanza molto ravvicinata.

Si legge nella relazione di servizio che verrà stilata dal brigadiere Montesi: indossava un impermeabile americano di colore olivastro, le braccia erano aperte e le gambe divaricate. Oltre al colpo alla schiena, presentava segni di una ferita d’arma da fuoco alla vena giugulare, verosimilmente il segno di un colpo di grazia.

Dall’assenza di macchie di sangue per terra, nonostante la recisione della giugulare, era facile intuire che l’omicidio fosse avvenuto altrove e il corpo lì trasportato o per dare un segnale o comunque per rendere noto a tutti che la vita di quel soggetto era finita per sempre.

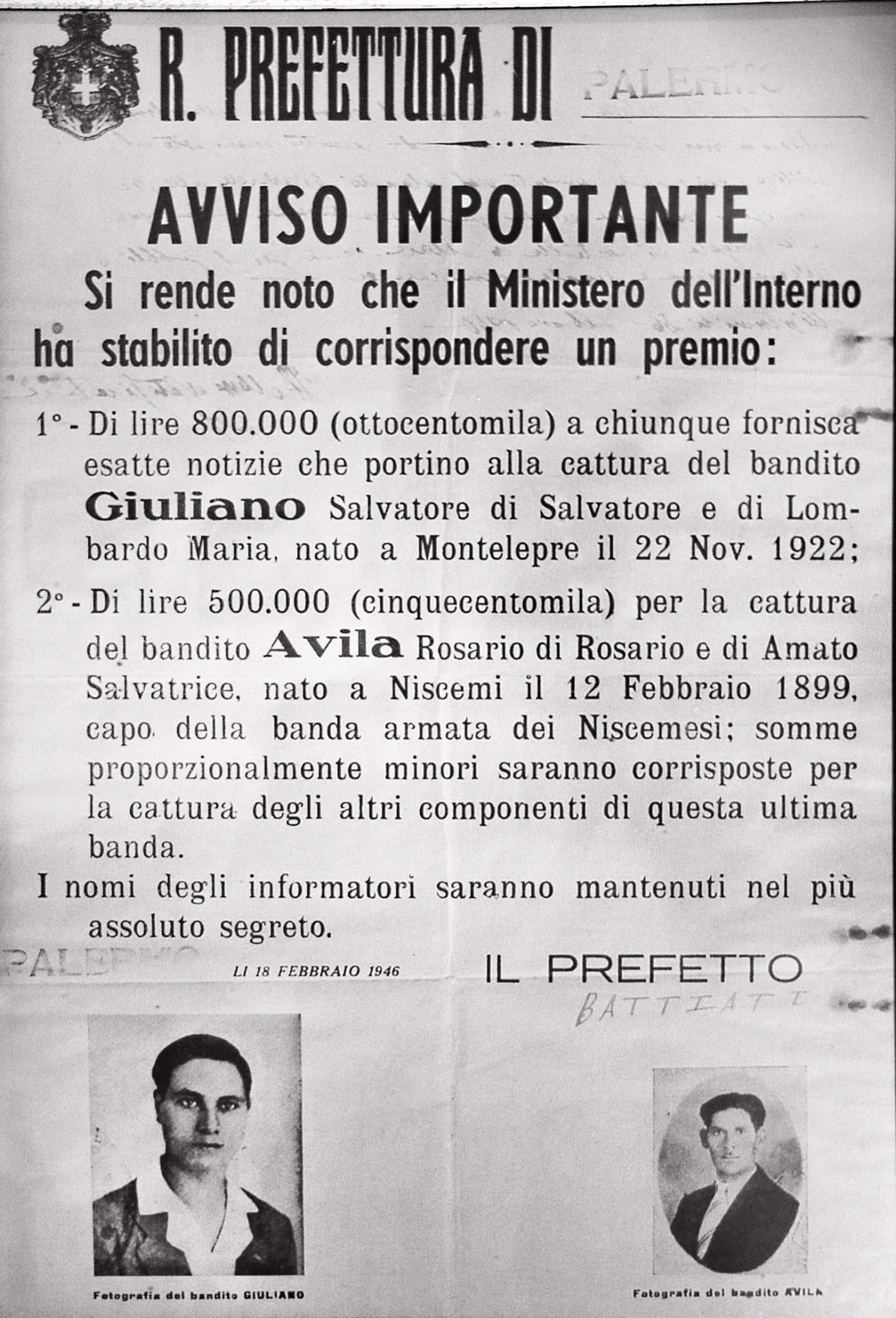

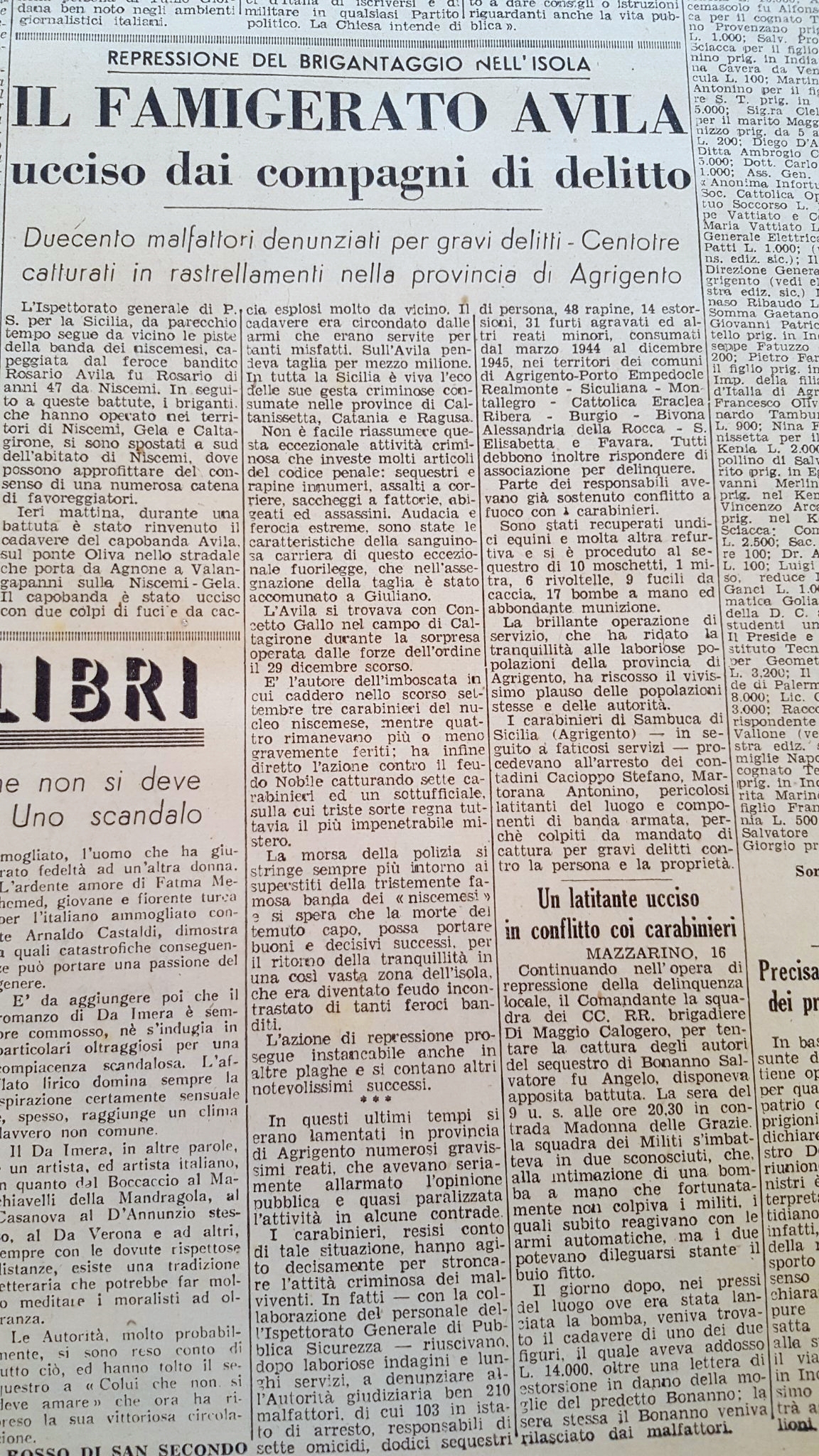

Qualcuno dei passeggeri azzarda timidamente un nome, anzi un soprannome, ma lo pronuncia così a bassa voce che nessuno lo capisce; gira attorno al cadavere e si accorge che a quell’uomo manca un pezzo dell’orecchio destro e l’ipotesi timidamente azzardata trova conferma: iddu è! “Iddu” è Avila Rosario, inteso Canaluni.

Per qualche attimo passeggeri ed autista si guardarono increduli senza sapere cosa fare, come se non fosse normale che occorreva avvisare i carabinieri che lì giaceva il cadavere dell’uomo più ricercato della Sicilia orientale: il secondo di tutta l’Isola, dopo il bandito Giuliano.

Avvertiti dunque i carabinieri, il sottufficiale presente in caserma (tale brigadiere Francesco Montesi) si precipitò sul posto, constatando che effettivamente quel corpo era del bandito che tutti cercavano.

Addosso aveva 300 lire e un copia del giornale La Libertà, bisettimanale separatista stampato a Catania. Per tanto tempo voce di popolo raccontava che avesse con sé ben 350 mila lire, pari a circa undicimila euro. Accanto giaceva un fucile mitragliatore.

Un carro normalmente adibito a trasporto di letame venne impiegato per condurre la salma in paese.

Nel frattempo il sistema del passaparola (efficace quanto il moderno WhatsApp) aveva avvisato tutta la popolazione di quell’evento straordinario. Un solo grido: Mmazzanu a Canaluni! E la gente cominciò ad affollarsi a largo Spasimo nel tentativo di poter vedere coi propri occhi che era finita l’epopea di questo personaggio che tanto terrore aveva seminato tra la popolazione.

Raccontano gli anziani che uno stuolo di bambini e ragazzi si accalcò in attesa del lugubre passaggio, quasi fosse una processione religiosa. E mentre ritmavano la frase, forse senza neanche comprenderne il significato, battevano le mani in modo cadenzato.

Ed ecco finalmente comparire il carro col suo macabro fardello, coperto da un pietoso lenzuolo, che occulta parzialmente quel corpo senza vita lasciando penzoloni quei grandissimi piedi che assomigliavano a due tegole (i canala) e che gli erano valsi il soprannome col quale era conosciuto in paese e non solo.

Scriverà il Corriere di Informazione in prima pagina la popolazione ha appreso con sollievo la fine del feroce bandito, che era il suo incubo.

In verità la maggior parte dei Niscemesi – almeno all’inizio dell’avventura banditesca – non aveva manifestato grandi preoccupazioni per le imprese di Canaluni, perché si diceva che la sua banda “toccava” solo i ricchi e non i poveri.

E i poveri erano la maggioranza assoluta! La mancanza di sangue e l’assenza di tracce di sparo fecero subito pensare che il delitto fosse stato commesso altrove.

Non si saprà mai dove, né chi intascò la taglia di 500.000 lire come corrispettivo di quell’orecchio, che la barbarie del tempo aveva promosso a macabro certificato.

Si parlò di qualcuno della sua stessa banda e qualche anziano a denti stretti pronuncia ancora ora un nome, dopo avere avuto reiterate rassicurazioni che resterà segreto.

Ma non c’è neanche certezza che la taglia sia stata effettivamente erogata. In una missiva segreta inviata dall’Ispettorato di polizia al ministero dell’Interno in occasione della morte dell’altro capobanda – Salvatore Rizzo – avvenuta il 19.2.1947 si legge: prego codesto ministero perché la taglia di 500 mila lire promessa per la cattura del capobanda dei Niscemesi venga concessa al confidente che è riuscito a far cogliere il bandito Rizzo Salvatore, capo della banda stessa, durante tutte le vicende dell’EVIS, in occasione dell’eccidio dei militari della stazione di Feudo Nobile e in tutte le altre imprese criminose.

La frase appare equivoca perché potrebbe significare che quella taglia promessa per Avila non era stata mai ritirata, ma potrebbe anche significare che la stessa somma data a chi aveva freddato Canaluni doveva essere data a chi aveva fatto trovare il nascondiglio di Rizzo.

Parafrasando quel che è stato detto di Giuliano, di sicuro c’è solo che Saru Canaluni è morto. Le indagini sulla morte di Avila non portarono a nulla, ma si sussurrava all’epoca che nessuno si prese la briga di sprecare il tempo cercando di capire da chi, come e dove fosse stato giustiziato.

Ma questo è solo il finale della storia della banda dei Niscemesi, per come è stata chiamata, della quale non si è scritto molto, salvo l’episodio di Feudo Nobile del quale si tratterà a parte e quel poco che è stato scritto è spesso frutto di approssimazione (si legge addirittura in qualche libro che il cadavere venne ritrovato nella strada che conduce ad Acate!).

Come in tutte le storie di Sicilia che hanno a che fare con banditismo o mafia non possono mai mancare i misteri, a volte grandi a volte piccoli, ma pur sempre inspiegabili.

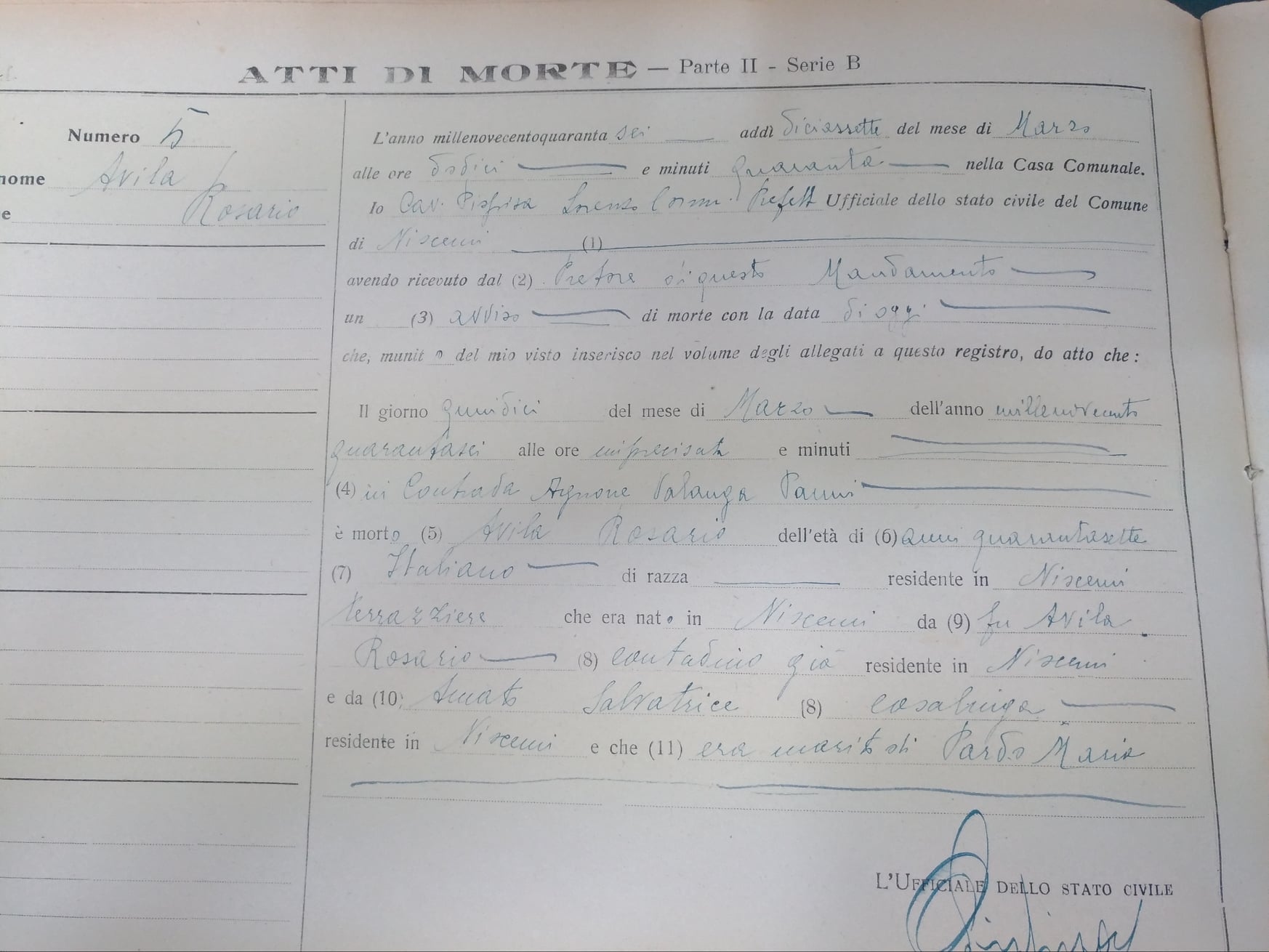

L’accanimento nella ricerca storica qualche volta dà i suoi frutti e in un sol colpo sembra che debba ribaltarsi un racconto oramai consolidato. Per come si è detto, il cadavere di Canaluni è stato rinvenuto il 16 marzo del 1946 lungo la provinciale che conduce a Ponte Olivo.

I carabinieri intervenuti redassero il rapporto all’autorità giudiziaria (allora era il pretore di Niscemi) che – come da prassi – diede comunicazione del decesso all’ufficiale dello stato civile del comune di nascita.

L’atto di morte di Avila è annotato al numero 5 del registro degli atti di morte, parte seconda, serie B e in esso si legge: l’anno 1946 addì 17 del mese di marzo alle ore dodici e minuti quaranta, nella casa comunale, io cav. Pispisia ufficiale dello Stato Civile del comune di Niscemi avendo ricevuto dal pretore di questo mandamento un avviso di morte con la data di oggi…do atto che il giorno quindici marzo 1946 alle ore imprecisate in contrada valanca del Panni (sic!) è morto Avila Rosario dell’età di anni 47, terrazziere, maritato con Pardo Maria.

Forse si sarà trattato di mero errore materiale da parte dell’ufficiale dello Stato Civile, ma errori e incongruenze si rinvengono anche in altri casi, segno che la storia di quel periodo meriterebbe un’attenta rivisitazione.

23.5.1946: Catturato a Catania il bandito Milazzo (che svelerà la fine degli otto carabinieri sequestrati a Feudo Nobile).

L’Ispettorato generale di pubblica Sicurezza della Sicilia aveva il compito di stanare i banditi e per riuscire nell’intento aveva assoldato un gran numero di confidenti, ai quali più che promettere denaro elargiva non meglio precisati favori; si trattava molto probabilmente di accordi inconfessabili e illeciti, ma nessuno in quel momento trovò qualcosa da ridire: si era in guerra e si badava più al risultato che al mezzo per conseguirlo.

Una ”soffiata” arrivò all’orecchio del dr. Ribizzi, funzionario di polizia: uno dei banditi responsabile del sequestro dei carabinieri (non si parlava ancora di omicidio) durante la latitanza andava a trovare una sua amante e così venne disposto un servizio di appiattamento proprio davanti la casa della donna. Viale Rapisardi a Catania è oggi una strada elegante, ma allora accanto a immobili di un certo pregio vi erano anche casupole fatiscenti.

Lo sguardo dei poliziotti appostati era tutto concentrato verso quel tugurio indicato, all’interno del quale doveva trovarsi l’adranita “lavanna ri pudditru” (questa la sua nciuria). Quando il sole comincia a levarsi in cielo, la porta sgangherata si apre ed esce un uomo, subito circondato: è iddu! Scrisse il cronista dell’epoca: sottoposto al più stringente degli interrogatori, il Milazzo confessò che gli otto carabinieri erano stati uccisi e dichiarò di aver partecipato lui stesso all’eccidio.

Perché il suo interrogatorio venne qualificato il più stringente non è dato sapere; non ci vuole però molta immaginazione per comprendere come l’aiuto del Milazzo venisse ritenuto indispensabile per trovare i carabinieri sequestrati e i mezzi convincenti usati apparvero adeguati all’importanza della notizia cercata.

Comunque sia, egli si dichiarò disposto ad aiutare la polizia al rinvenimento di quel che restava dei militari. E così due giorni dopo, accompagnato da carabinieri e polizia al comando del commissario Giuseppe Ribizzi, comandante dei nuclei mobili dell’ispettorato di p.s. per la Sicilia orientale e del commissario Melfi, il bandito catturato condusse gli inquirenti in quel cimitero improvvisato.

Un militare si calò con la corda, ma risalì poco dopo dicendo di non avere trovato nulla. Era ovvio che non poteva essere così: come immaginare che il Milazzo avesse voluto prendersi beffa di tutte quelle autorità? A quale scopo? Dopo qualche cenno di testa del bandito, il commissario Melfi e un carabiniere si calarono di nuovo dentro quella fossa e dopo avere scostato alcune grosse pietre, fra i detriti apparvero, sotto la luce di una torcia, i miseri resti di quel terribile sterminio.

Scesero altri tre carabinieri, ma il forte odore impedì di proseguire nelle ricerche, per cui vennero fatti giungere mezzi adeguati e quel che restava degli otto disgraziati venne portato in superficie. Le operazioni si completarono il 27 maggio e il posto venne piantonato giorno e notte.

Scriveranno i giornali: diversi metri cubi di terreno furono estratti assieme ai cadaveri. Questi apparivano come mummificati, ischeletriti: pesavano sui trenta chili ciascuno. Presentavano tutti una larga ferita all’occipite e numerosi colpi d’arma da fuoco avevano squarciato i loro petti, colpi tirati a distanza ravvicinata. I volti erano sfigurati ma non irriconoscibili.

Caricate su un camion, le casse furono trasportate a Mazzarino, dove ricevettero la benedizione. Indi, salutate al passaggio da due fitte ali di popolo commosso e riverente, furono avviate a Caltanissetta, dove furono loro tributate solenni onoranze.

25 ottobre 1975 muore l’ultimo bandito “Rocco” Buccheri

Uno dei personaggi di spicco della Banda dei Niscemesi era un certo Vincenzo Buccheri, la cui storia merita tutta di essere raccontata. Dopo l’uccisione di Canaluni e di altri affiliati, il Buccheri era sfuggito più volte alla cattura. Sulla sua testa era stata messa una taglia di 500 mila lire, ma l’allora cinquantanovenne bandito era introvabile e così il 18 gennaio 1966 la taglia venne raddoppiata: un milione di lire a chi avesse fornito notizie dell’oramai ex bandito, ricercato da quasi vent’anni. Dopo la morte del capobanda si era tentato in tutti modi di stanarlo. Un giorno l’allora comandante dei carabinieri di Niscemisi recò nella chiesa Madre e pregò il parroco Galesi di intercedere per convincere il Buccheri a costituirsi. Sebbene riluttante e timoroso, il prete fece qualche passo, interpellando coloro che sapeva essere in contatto col bandito. E il messaggio venne recapitato, ma la risposta fu tutt’altro che positiva: dite a quel prete che si faccia gli affari suoi . Intanto si era sparsa la voce, fatta adeguatamente arrivare alle orecchie degli investigatori, che Buccheri era emigrato in Brasile: ben presto però si capì che era un semplice depistaggio. Sul suo capo pendevano due condanne all’ergastolo emesse dalle corti di assise di Catania (nel 1958) per i tre carabinieri uccisi nell’abbeveratoio di fonte Apa e di Caltanissetta per la strage dei carabinieri di Feudo Nobile (nel 1953); in totale gli furono addebitati : 11 omicidi, 35 rapine, 9 sequestri di persona e 3 estorsioni. La notizia venne resa nota dalla Stampa di Torino (19.1.1964) secondo la quale voci popolari lo davano residente a Genova, dove vivevano la moglie Gaetana Lombardo (che gestiva un negozio di generi alimentari) e i loro figli Giuseppe, Salvatore e Felice. Quest’ultimo aveva una sala da barba nel capoluogo ligure ed era lì che avveniva spesso l’incontro col padre e gli altri congiunti. Ma la signora Lombardo – sposata Buccheri – sosteneva di essere vedova. E in effetti le perquisizioni a casa della donna, ripetute nel tempo, non davano alcun esito, rinvenendo la vedova del bandito da sola o qualche volta in compagnia del cognato Rocco. Ma per assistere al colpo di scena occorrerà ancora aspettare un altro ventennio. Infatti il 25 ottobre 1975 muore nella città ligure, nella clinica privata Montallegro, “Rocco” Buccheri, fratello di uno dei più ricercati latitanti d’Italia, le cui foto erano affisse in tutti i posti di polizia. Era sofferente di cirrosi e scompenso cardiaco. Dopo la cerimonia funebre, viene svelato l’arcano: non era Rocco il morto (deceduto in realtà nel 1973) ma proprio l’ex bandito ricercato, che aveva assunto l’identità del fratello! Si era trasferito nel 1947 a Genova in via Canepari 21, dove lavorava come muratore in alcuni cantieri edili e la notte faceva il guardiano. Era descritto da tutti come una persona irreprensibile (La Stampa 28 ottobre 1975). In effetti i due fratelli si somigliavano molto e avevano entrambi una cicatrice sul volto (uno però a destra e l’altro a sinistra). Con la morte di Buccheri, tutti i componenti della Banda erano scomparsi. E anche la loro storia sembrò inabissarsi nella popolazione niscemese, marchiata col sigillo indelebile del feroce banditismo del dopoguerra.

La ricostruzione che si propone al lettore è frutto di ricerche documentali ma soprattutto della testimonianza di quanti hanno vissuto quei giorni, sebbene ancora oggi è facile rinvenire una certa ritrosia nel parlarne, segno della efferatezza della banda e del timore di vendette, sebbene siano trascorsi oramai oltre settant’anni.

Per gentile concessione dell’autore:

Giuseppe D’Alessandro

La banda dei Niscemesi. La vera storia dei fuorilegge più sanguinari del dopoguerra.

Editore Youcanprint

E’ possibile acquistare il libro su:

16.10.1945 Three carabinieri killed in the Apa district (Niscemi)

At first the Niscemese gang had operated in the Niscemi territory, raiding what they could: hundreds of people had been robbed, the farms looted and no one wanted to go to live in the countryside. The rich never left the country and those who set out on the road were aware of the risk they ran.

Being escorted meant only endangering the lives of other people, especially along the road that leads to Caltagirone, particularly beaten by bandits.

The roundups carried out by the Carabinieri bore little fruit. Only on one occasion did they achieve a significant result: a bandit wounded, one captured and another constituted himself to the military (the calatino Angelo Vigoroso); all after a shooting in the Piana di Gela.

Towards the end of 1945 the actions of the gang became more and more enterprising and constituted a taste of what would happen in January of the following year: the massacre of Feudo Nobile.

On October 16, 1945, a dozen bandits stationed themselves along the little road that branches off from what the Niscemese still call today “the curve ri the Apa” and leads to the source that takes the same name (“bbrivatura ri l’Apa” ).

We will learn later from the hands-on voice of Canaluni’s son that Giuseppe Militello (who will lose his life on another occasion by shooting a petrol drum in the act of carrying out an attack on the engineer Iacona) was leading that squad.

Twenty years later, one of the carabinieri involved in the ambush will also tell the story: Santo Garufi. Also reached in the head by machine gun shots, albeit from a graze, he fell wounded and his body covered by a dead colleague.

The bandits approached and the Garufi begged them: what more do you want! At that point the Militello shouted to his friends enough! simultaneously raising his hand to crush any attempt to open fire.

Then he ordered the soldier to get up, but not having the strength someone helped him to do so, lifting the dead body that covered him. A bandit asked him in a peremptory voice: where is Brigadier Montesi? They were disappointed to learn that he was not in the group.

Garufi will explain that the deputy brigadiere Montesi was in force at the mobile nucleus of Niscemi and was a real bugbear for the bandits. It will be the carabiniere who will be the first to arrive on the spot where the lifeless body of Canaluni was found.

From this testimony it is easy to understand how the ambush actually aimed at killing the brave non-commissioned officer. After a brief conciliabolo, the bandits decided to leave the survivor alive and after having stolen his coat, shoes and weapons they ordered him to leave.

With a disconcerting detail: they ordered the injured carabiniere to take off the shoes of dead colleagues. It will later be known that the stolen weapons (muskets mod. 1891) were brought to Monte San Mauro and delivered to Concepts Gallo.

Here they were assigned to the Separatists by lot. While fearing at any moment of being shot in the back, the carabiniere Garufi set out for the town, while the criminals plundered what remained of his dead colleagues.

Although wounded, he managed to arrive at the barracks around midnight and from there he was taken to the hospital. The other survivors also arrived in dribs and drabs, while one went to Caltagirone to be treated in the hospital. An investigation followed and thanks to the testimonies of the survivors it was learned that Rizzo, Buccheri, Collura, Arcerito, Romano, Bottiglieri, Lombardo, Leonardi, Interlandi and Milazzo had taken part in that fire.

In addition to Avila junior, the aforementioned Militello who acted as head, a certain Buscemi, who was never exactly identified and perhaps someone else. It also seems that Avila the father was among the bandits, but of this – due to the darkness – there was never certainty.

The bandit indicated with the surname Milazzo will have a decisive role in the discovery of the bodies of the carabinieri seized at Feudo Nobile. At first, the head of EVIS Concepts Gallo was suspected as the instigator of that massacre, because he had theorized the attack against the Carabinieri, as they represented the “Italian State”.

Even in the report drawn up by General Branca and sent to the head of the government Alcide De Gasperi, Gallo is mentioned as the one who had “personally” led the band of bandits (report dated 16.2.1946).

At the trial, however, he was acquitted, because he was able to prove that that day he was at the Monte San Mauro field. Avila Saro, son of Canaluni, was arrested six months later and gave some names of his accomplices (including his father), omitting to mention both Rizzo and Milazzo.

Gesualdo Collura instead – who was also arrested – admitted his presence in the group, but denied having participated in the shooting, declaring that he had gone away to fetch the horse of another bandit, the Milazzo.

The latter will eventually confess the wrongdoings and confirm the names of the accomplices. At first he even mentioned the name of another bandit, that Salvatore Di Franco, but in the end he was not even tried; he was found dead on August 9, 1945.

28.12.1946: The “battle” of Monte San Mauro

Less than twenty kilometers from Niscemi, in the territory of Caltagirone, there is a place called Monte San Mauro, but for the Niscemese it has always been “a muntagna ri san Moru”.

It is an archaeological site of considerable importance, dating back to the Bronze Age. Archaeologists have speculated that in the past there was an acropolis and a princely residence, later reused by the Greeks.

In Niscemi the elderly tell a legend according to which in that locality there is a series of underground galleries full of treasures, but whoever enters and takes something precious can no longer find the exit. But Monte San Mauro is known because it was there that the military epic of EVIS ended, with the capture of the chief Concept Gallo.

But why in Caltagirone? Here too there is an “official” story and the versions that are told, which differ from the canonical narrative. To understand what happened and why it happened in that very place, we need to take a step back and go back to the moment of the killing of the military leader Antonio Canepa (June 17, 1945).

The military leaders feared a reaction from the Independents and not only reinforced the garrisons that were hunting the Separatists, but built a network of collaborators in an attempt to track them down.

But the opposite front also had its 007s, so they were warned that the Cesarò camp, which was the base of EVIS, had been discovered and were forced to migrate quickly to another place. This was identified precisely in San Mauro, where Concepts Gallo’s wife (Gueli Adriana) owned land.

In any case, on December 27, 1945 some informants reported that the base camp was located in that locality of Calatino and a superficial incognito reconnaissance confirmed the truthfulness of the news: to be exact, Monte Moschitta, south-west of Caltagirone, altitude 530 meters (so we read in the military maps).

The number of separatists was around sixty (but this will become known later) however the “morsel” was delicious because there was also that Gallo Concept that had taken the place of Antonio Canepa, the legendary Mario Turri; and the devotion to the deceased commander was so great that Gallus wanted to take the battle name of Secondo Turri. Gallo’s appointment was made by acclamation on 1 July 1945: he was just 32 years old. And so on December 29 of that year military operations began with the creation of two columns: one (made up of 100 infantrymen, 200 carabinieri and two tanks) that starting from Catania would have directly attempted the assault and the other formed by 200 carabinieri, coming from Syracuse, with the task of blocking any escape.

Concept Gallus, like a true military leader, often harangued his men; on one occasion he reassured them by telling them that in the event of capture by the “enemy” the fighters would be treated according to international conventions as the GRIS guerrillas were credited as belligerents.

THE GRIS (Revolutionary Youth for the Independence of Sicily) was nothing more than the name given to the independence army (EVIS) after Canepa’s death. Basically it was the continuation, so the two terms are to be considered indicating the same organism.

According to what the Unit wrote on the eve of the trial against Concepts Gallo (11 July 1950) it was Salvatore Giuliano who a few hours after the assault on the Bellolampo barracks (26.12.1945) sent a courier on horseback with a letter to be delivered to Gallo, with which he was warned that in a few days the Italian army would intervene en masse in Monte San Mauro. The letter was allegedly confiscated from the head of EVIS. Years later, Giacomo Balistreri from Niscemi will recall those times in an interventionist at Rai (at minute 7

The battle was very bloody and there were so many shots fired that the ammunition ran out, so the conflict resumed the next day, after the arrival of supplies (which had prudently been crammed into a garrison in Caltagirone).

The war ended around noon the next day. At the end, the Independents captured were just four (including the boss), six machine guns, 3000 cartridges, some rifles and muskets, a Fiat 1100 and some head of cattle believed to be stolen were seized.

A police officer (Giovanni Cappello di Santa Croce Camerina) was killed on the field and four soldiers were wounded: the infantry lieutenant Giovanni Corcione, the deputy police sergeant Maugeri and the infantrymen Giuseppe Corallo and Giuseppe Privitera. According to the version of the Separatists, the soldier was killed by a bullet fired by the carabinieri themselves.

Among the evists, such Emanuele Diliberto of Palermo lost his life and five were wounded. Between them two Niscemese bandits. Also perished was a peasant (a certain Cataudella) riding a white mare, perhaps mistaken for Gallo, who had a similar animal. The final budget, however, was very meager for the state.

It is true that the military leader had been captured, but it was also true that the bulk of the evisti (and the bandits) had managed to escape. And among these – reads the report – all the members of the Niscemese gang!

Even the figures appear merciless: on the one hand, 500 “professional” soldiers commanded by three generals (Concept Gallo wrote in his memoirs that there were five generals) against less than sixty “irregular”! At the time of the interrogation Gallus made partial admissions, but refused to reveal compromising details.

He admitted that he was the leader and that he obeyed a supreme command, without adding any detail, disdainfully excluding that the attacks on the Palermo barracks were attributable to the separatists and that the presence of brigands in the camp was only occasional and fortuitous.

As for the financing of the “troops”, he replied that the proceeds came from spontaneous donations and “requisitions” that he himself ordered.

The organization of life inside the camp was described by several participants: the leader was Gallo, who called himself commander and his deputy – who had the rank of lieutenant – was Nino Velis who will then take his place.

The whole camp was surrounded by checkpoints armed with machine guns and 24 hours a day there was an inspection patrol.

Under the direct dependence of Gallo and Velis there were “sergeants” and under “corporals”. When Gallus was questioned – probably to give himself more importance – he stated that his “army” was made up of various brigades of one hundred men each and that each brigade included ten squads.

Despite the precautions taken, a few strangers crossed over into the camp. In this case, a rather singular protocol had been prepared: fearing that it could be undercover infiltrators or carabinieri, whoever was caught nearby had to be captured, blindfolded and brought before the commander.

During the journey – and here lies the singularity – the evists had to confabulate among themselves, but making themselves heard by the captured, evoking tanks, artillery pieces and other untrue details, in order to bring out a much more powerful image of that “army”.

It was also learned that someone “deserted” in the middle of the night and for this he was pursued, fearing a denunciation. The names were also known: Umberto Camuri, Francesco Paolo Ghersi and Umberto Siracusano.

Another stratagem to be used in the event of a battle (which then happened) was to constantly move the repeating weapons, in order to give the feeling that they were far superior to the actual ones. This tactic actually had some results: the “Italians” were convinced that the first clash had occurred only with an outpost and not with the entire “army”.

The story of the Gallo Concept

When Concept Gallo, the EVIS military leader captured in Monte San Mauro, decided to talk years later, he reported that when he moved to Caltagirone he found the area “haunted”, especially by the Niscemese gang, although some other local outlaw hung out there mashed potato.

Then he began to make contact with the various criminal groups, signing pacts of non-belligerence to which many adhered.

He also told of a case of firefight between Separatists and bandits and some of these left their pens. In fact, on 22 June 1945 on Mount Soro, the highest peak of the Nebrodi, the sighted Francesco Ilardi with other fellow soldiers had a firefight with the gang of Giovanni Consoli who, abusing the name of the EVIS, carried out extortion. “And the police became beautiful …” he concluded ironically.

Some criminals even showed up as a volunteer in the field and at that point Gallo had to choose, not being able to fight between two fronts: bandits and carabinieri.

Then speaking of the Canaluni gang, he said that once he had Rosario Avila tied naked to a tree because he had behaved badly.

Obviously we don’t know how much truth there is in his words. Just as we cannot be sure that he says the truth when he declares that “the bandit Rizzo, portrayed as a ferocious man, was in fact helpful and very devoted”.

In an interview granted after many years he will also talk about the income deriving from the sale of his oil, adding that after the battle 25 quintals disappeared. Those who then donated basic necessities were given a receipt with the Evis stamp and the signature of Gallo under the pseudonym “M.Turri”.

The receipts were numbered and dated and each one specified whether the donations were “voluntary” or “forced”. Obviously, questions about the separatist-bandit mix were pressing.

Gallo’s response was very evasive: he spoke of six “criminals” who had been welcomed into the camp, but that at the time of the battle half had gone away, while those who remained actively took part in the conflict. He admitted that during the night the bandits left the camp to commit crimes, but as far as he knew they were not accompanied by the evista in the raids.

As for the moments of his arrest, he remembers being stunned by a bomb and finding himself blocked by some carabinieri. Finally, he confirms the exact number of his “soldiers”: 53 plus 3 bandits.

A cipher was found on Gallo, several letters signed “Vento”, a false card in the name of a certain Franco Buscemi and a false license.

In one of these letters, dated December 2, 1945, a stranger, whose name Gallo refused to mention, warned him that five hundred men had been sent against him (proving that Evis had an intelligence service). To confirm that the Gallus depended on a “supreme command”, the letter concluded as follows: if successful, warn and wait for orders before continuing.

It took almost thirty years for Gallo to reveal the author of that letter: in an interview released in 1974 he said that the head of the military command on which he depended and therefore the author of that letter that announced the attack and that “Vento” stopped was Guglielmo Carcaci, separatist and nobleman, belonging to that political wing which by convention is called “right”.

In parallel, negotiations were underway between the MIS and the Italian government: in Rome with the minister Romita and in Palermo with General Berardi, military commander of the island.

The Separatists were aware that the situation could precipitate a bloodbath and so they proposed to the senior officer the idea of putting a vast amnesty on the plate, especially in favor of young people who had joined the EVIS (or GRIS who if you prefer), leaving the bandits out of the leniency provision and above all leaving the repressive forces free to act towards them.

These semi-clandestine negotiations gave the impression that the general was a weak person, to the point of believing that the clash of Monte San Mauro would not have obtained the desired outcome because the orders given would have been to behave mildly, without forcing one’s hand.

Moreover, Carcaci had reached an agreement with the latter: there would be no military intervention in the San Mauro camp as long as the negotiations were in progress. But this was not the case.

And when the assault happened, Carcaci rushed hard-nosed to the general, who apologized by saying that the order had been given by Aldisio, taking advantage of his absence from the island.

This is what he tells in an interview, in which he retraces what happened that day and the story appears imbued with self-referentiality for the narration of heroic moments that probably never happened.

Gallus speaks of a bullet that hit him in the chest, but was deflected by a medal, of a shot from a machine gun that just came out of his jacket and a shot from a rifle that made his cap fly, leaving him unscathed.

At this point, given the imminent end, he decided to commit suicide, taking a hand grenade out of his pocket and throwing it at his feet.

But the bomb did not explode. He continues his fictional story: I fainted and a soldier was about to shoot me with a barrage of machine guns, when Marshal Manzella intervened, who turned to the soldier and said “if you shoot at that man I’ll kill you”.

He was then handcuffed and taken to his cell, where he was alone for two days, without food or water. Together with him, two separatists were captured: Amedeo Boni and Giuseppe La Mela.

He also told an unprecedented episode: one of the generals who commanded the troops complimented his father (also a separatist and elected mayor of Catania in the 1950s) saying I had the honor of shaking his son’s hand.

Is it truth or is it an invention put around to create a myth? We will never know: certainly his people revered him, to the point of nicknamed him u liuni di santu Mauru.

Totò Salerno was one of the protagonists of the battle.

In the interview released by Gallo it is reconstructed how, when and why the meeting with the “bandits” and with Giuliano in particular takes place. As anticipated, everything happens after the death of the first head of Evis, Antonio Canepa.

This is the story of Gallo, who speaks in the first person: On June 17, as I am about to leave Catania, I receive a phone call from Guglielmo Duke of Carcaci, commander of the Youth League and commander general of EVIS.

He tells me: «They killed Canepa. Do not move. I’ll come and get you ». We left together towards Cesarò and took refuge in the duchy of Wilson, near Bronte. After a few days, a car arrives. At the helm is an admiral of the United States Navy.

Next to a beautiful lady. Behind, William of Carcaci wearing a commodore’s hat (a sort of admiral – n.d.a.). I hurry into the car, put on a United States admiral’s jacket, put the commodore’s cap on my head and the car starts.

The city is surrounded by police and carabinieri. A real garrison with checkpoints everywhere. Everywhere men and barriers that are raised only after the police have checked the documents of those who want to leave the city. We arrive at the Ognina checkpoint. The admiral makes himself recognized and the carabinieri patrol gives us a perfect salute by opening the barrier.

Here Gallo and the others are hosted by the US military command and here he talks to men of the Secret Service with stars and stripes. The result is a loud reflection: Americans look favorably on the separatist movement! The story then continues with the meeting between Gallo himself and the leader of the gang, the “mythical” Salvatore Giuliano.

It all stems from a meeting in Palermo, during which the separatists are divided into two factions: those who intend to give up the armed struggle and those who want to keep it until they gain independence.

In the end, no decision is made. At that point, Gallo asked another prominent member of the Movement, Count Tasca, to meet Giuliano in order to find accommodation for the young people of EVIS in his area, in case of need.

The answer is ironic: yes, now dial the phone number and Giuliano answers you. The next day, Gallo – together with three other people – sets off to search for the impregnable bandit.

He succeeds: he meets Giuliano and is surprised to see him alone, since the newspapers describe him as always accompanied by bodyguards. The two knew each other only by fame: they greet each other and soon a relationship of respect was born, which immediately became sympathy.

But the two have a different past and also a present and this difference can also be seen in the relational language: Gallo speaks to Giuliano and he reciprocates with the classic Vossia. Now I sleep for an hour and you keep watch. Then, when I wake up, he dozes off. And gives him the machine gun. Thus began the marriage between the band and Evis.

The two stay together for two days and leave with these words pronounced by Concepts Gallo: I promise you that if you behave well in this fight, forgetting everything else and looking at the ideal of independence, only that, I promise you that if we win we will have a fair consideration for you and you will be judged for what your true faults are.

Gallo – after almost thirty years – still wants to mark the distance. There is much discussion on this point.

And he says he wanted to keep the aims of the two teams very distinct: you see, you are here above the mountains for your reasons; we are in the mountains for other reasons.

We could have a great time in our homes. Instead we decided to fight for an ideal of freedom and independence. Freedom and independence that if Sicily had had before, would have affected its economic development and, certainly, you, today, would not be here, in this situation.

The goodbye of the Rooster will actually be a farewell and after a hug Turiddu reassures him. In his own way: Cu is up to vossia mori.

Doubts about Gallo’s story

How much truth there is in the story of the former military leader is not known; he certainly tells the truth when he says that Evis needed peace of mind to operate as an underground army and certainly could not be crushed by the roundups of the carabinieri on one side and by the raids of bandits on the other.

It was therefore a tactical choice rather than a strategic or organic one, if you prefer. The number of Italian soldiers he had to face in San Mauro was certainly imaginative: it speaks of five thousand men (in reality the figure must be reduced by 90%), of five generals (in reality there were three), of reconnaissance aircraft and of much other.

The interview becomes “hot” when the subject of the mafia is touched upon. Gallo does not deny that Don Calo ‘Vizzini also joined the MIS, indeed it seems he went around with the Trinacria coat of arms. But this instrumental adhesion did not last very long: soon the Mafia – in Gallo’s words – will ferry in a very specific political party. Besides, it didn’t make any military sense in a group that didn’t have power …